All great base stealers have a love of larceny. They derive joy from picking the opposing team's pockets, especially in pressure situations. To excel as a base thief, you have to be cocky. When you get to first base, your body language and demeanor should announce, "I am stealing and there is nothing anyone can do to stop me!" You have to embrace the role of intimidator.

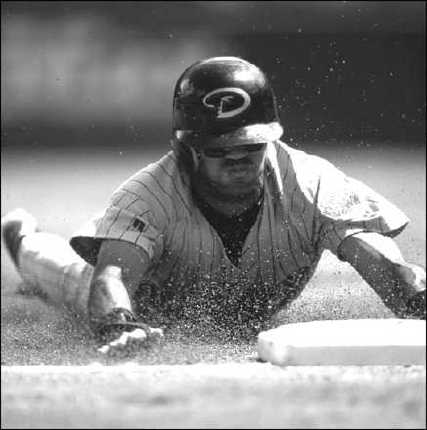

Stealing a lot of bases with your team far ahead or behind doesn't mark you as a great thief. Far more valuable are the runners like Tony Womack (see Figure 1), who ignite their offenses by stealing in the early innings or during the late portions of a close game.

|

Figure 1: Premier base stealer Tony Womack. |

A good base thief should be successful on at least 75 percent of his stolen base attempts. If your percentage is below that, your attempts are probably hurting your team.

Reading the pitcher

Ninety percent of all stolen bases come off the pitcher rather than the catcher. If you waited until the pitch reached home plate before you tried to steal, you would be thrown out 95 percent of the time. However, if you get a good jump as the pitcher delivers the ball, a catcher can do little to get you out, even if you aren't blessed with exceptional speed.

Base runners should study the opposing pitcher the moment he takes the mound:

- See if he has two distinct motions: one when he throws home and another when he tosses the ball to first to hold a runner on.

- Watch the pitcher throw to the plate from the stretch; note what body parts he moves first.

- See whether he does anything different when he throws to first base.

- See if he sets his feet differently on his pick-off move.

- Try to detect any quirk that can reveal the pitcher's intentions.

Ironically, good pitchers are often the easiest to steal on. Erratic pitchers typically use different release points from pitch to pitch (which is why they are erratic). You never know when they are going to let go of the ball. But the better pitchers have purer mechanics. They establish a rhythm and stick to it.

Pedro Martinez, the American League Cy Young Award winner in 1999 and 2000, does the same thing to get to his release point on nearly every pitch. So a runner may be able to spot some clue in his motion when he plans to throw to first base.

After you have a pitcher's pattern down, take off for second the moment he moves toward his release point. He might indicate this with a hand gesture or some slight leg motion. Even a pitcher's eyes can fall into a pattern. Many pitchers take a quick glance toward first before throwing home; when they don't sneak a look toward you, they are throwing to your base.

You can also figure out pitchers by observing their body language. Watch the pitcher's rear leg. If it moves off the rubber, the throw is coming toward you. To throw to the plate, every pitcher must close either his hip or his front shoulder. He must also bend his rear knee while rocking onto his back foot.

After the pitcher does any of these things, the rules state he can no longer throw to your base. You should immediately break for the next bag. If the pitcher breaks his motion to throw toward any base, the umpire should call a balk, which allows you and any other baserunners to advance.

If you are on first base, left-handed pitchers are traditionally harder to steal on than right-handers because the lefty looks directly at you when he assumes the set position. However, this also means you are looking directly at him so he is easier to read — if you know what to look for. Scrutinize his glove, the ball, and his motion.

If a southpaw tilts back his upper body, he is probably throwing to first; a turning of the shoulder to the right usually precedes a pitch to the plate. When he bends his rear leg, he is most likely preparing to push off toward home.

When a righty is on the mound, observe his right heel and shoulder. He cannot pitch unless his right foot touches the pitching rubber. Throwing to first requires him to pivot on that foot. If he lifts his right heel, get back to the bag. An open right shoulder also indicates a throw to first.

Lead — and runs will follow

Base thieves can choose between a walking lead and a stationary lead. Lou Brock, the former St. Louis Cardinals outfielder, used a walking lead. Brock was faster than most players, but he wasn't especially quick out of his first few steps (most taller players find it difficult to accelerate from a dead stop). He would walk two or three small steps to gain momentum before taking off toward second base.

If you require a few steps to accelerate, this is the lead for you. A walking lead does, however, have one disadvantage: A good pitcher can stop you from moving by simply holding the ball. If you continue to stroll, the pitcher can pick you off.

For that reason, some prefer the stationary lead, when a batter takes a few strides off first base then stands still while the pitcher prepares to throw. The pitcher can still hold the ball, but the batter is not budging until the pitcher makes his first move to the plate.

Whichever baserunning lead you choose, use the same one whether you are stealing a base or not. Set up the same way on every lead. You don't want to telegraph your intentions to the pitcher. He's watching you for clues as closely as you are watching him.