Integration is a fundamental part of calculus. If you want to become a fully integrated person (as opposed to a derivative one), integrate these integration rules and make them an integral part of your being.

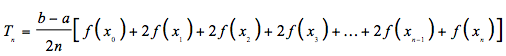

The trapezoid rule

The trapezoid rule will give you a fairly good approximation of the area under a curve in the event that you’re unable to — or you choose not to — obtain the exact area with integration.

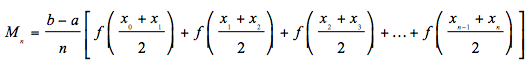

The midpoint rule

An even better area approximation is given by the midpoint rule — it uses rectangles.

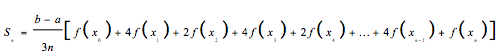

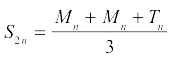

Simpson’s Rule

The best area estimate is given by Simpson’s Rule — it uses trapezoid-like shapes that have parabolic tops.

If you already have, say, the midpoint approximation for ten rectangles and the trapezoid approximation for ten trapezoids, you can effortlessly compute the Simpson’s Rule approximation for ten curvy-topped “trapezoids” with the following shortcut:

This gives you an extraordinarily good approximation.

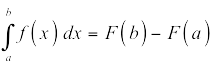

The definite integral

In essence, what all definite integrals,

do is add up an infinite number of infinitesimally small pieces of something to get the total amount of the thing between a and b. The expression after the integral symbol,

(the integrand), is always a mathematical expression of a representative piece of the stuff you’re adding up.

The indefinite integral

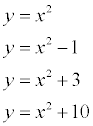

The indefinite integral,

is the family of all antiderivatives of

That’s why your answer has to end with “+ C.” For example,

is the family of all parabolas of the form

such as

and so on. The derivative of all of these functions is 2x.

A rectangle’s height equals top minus bottom

If you’re adding up rectangles with a definite integral to get the total area between two curves, you need an expression for the height of a representative rectangle. This should be a no-brainer: it’s just the rectangle’s top y coordinate minus its bottom y coordinate.

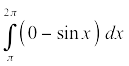

Area below the x-axis is negative

If you want, say, the area below the x-axis and above

between

and

the top of a representative rectangle is on the x-axis, the function

and its bottom is on

Thus, the height of the rectangle is

and you use the following definite integral to get the area:

which equals, of course,

So this negative integral gives you the ordinary positive area. And that’s why an ordinary positive integral gives you a negative area for the parts of a curve that are below the x-axis.

Integrate in chunks

When you want the total area between two curves and the “top” function changes because the curves cross each other, you have to use more than one definite integral. Each place the curves cross defines the edge of an area you must integrate separately. (If a function crosses the x-axis, you have to consider

as the second function and the x intercepts as the crossing points.)

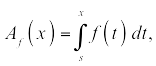

The fundamental theorem of calculus, take 1

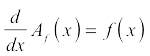

Given an area function

that sweeps out area under

namely

the rate at which area is being swept out is equal to the height of the original function. So, because the rate is the derivative, the derivative of the area function equals the original function:

The fundamental theorem of calculus, take 2

Let F be any antiderivative of the function f; then