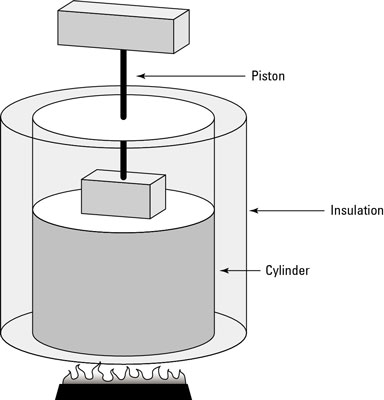

In physics, when you have a process where no heat flows from or to the system, it’s called an adiabatic process. The first figure shows an example of an adiabatic process: a cylinder surrounded by an insulating material. The insulation prevents heat from flowing into or out of the system, so any change in the system is adiabatic.

Examining the work done during an adiabatic process, you can say Q = 0, so

equals –W.

The minus sign is in front of the W because the energy to do the work comes from the system itself, so doing work results in a lower internal energy.

Because the internal energy of an ideal gas is U = (3/2)nRT, the work done is the following:

where Tf represents the final temperature and Ti represents the initial temperature. So if the gas does work, that work comes from a change in temperature — if the temperature goes down, the gas does work on its surroundings.

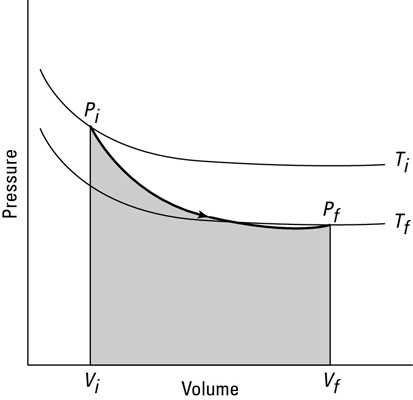

You can see what a graph of pressure versus volume looks like for an adiabatic process in the second figure. The adiabatic curve in this figure, called an adiabat, is different from the isothermal curves, called isotherms. The work done when the total heat in the system is constant is the shaded area under the curve.

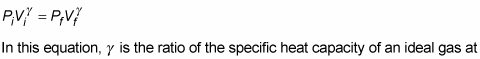

In adiabatic expansion or compression, you can relate the initial pressure and volume to the final pressure and volume this way:

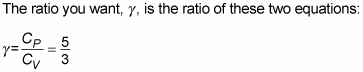

constant pressure divided by the specific heat capacity of an ideal gas at constant volume (specific heat capacity is the measure of how much heat an object can hold):

How can you find those specific heat capacities? That’s coming up next.

To figure out specific heat capacity, you need to relate heat, Q, and temperature, T. You usually use the formula

represents the change in temperature.

For gases, however, it’s easier to talk in terms of molar specific heat capacity, which is given by C and whose units are joules/mole-kelvin

With molar specific heat capacity, you use a number of moles, n, rather than the mass, m:

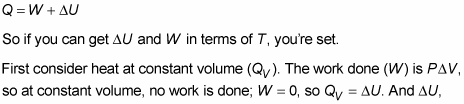

To solve for C, you must account for two different quantities, CP (constant pressure) and CV (constant volume). Solved for Q, the first law of thermodynamics states that

the change in internal energy of an ideal gas, is

Therefore, Q at constant volume is the following:

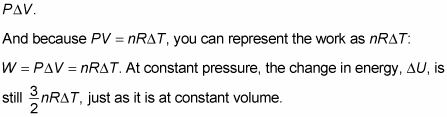

Now look at heat at constant pressure (QP). At constant pressure, work (W) equals

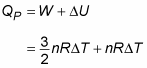

Therefore, here’s Q at constant pressure:

So how do you get the molar specific heat capacities from this? You’ve decided that

which relates the heat exchange, Q, to the temperature difference,

via the molar specific heat capacity, C. This equation holds true for the heat exchange at constant volume, QV, so you write

where CV is the specific heat capacity at constant volume. You already have an expression for QV, so you can substitute into the earlier equation:

Then you can divide both sides by

to get the specific heat capacity at constant volume:

If you repeat this for the specific heat capacity at constant pressure, you get

Now you have the molar specific heat capacities of an ideal gas.

For an ideal gas, you can connect pressure and volume at any two points along an adiabatic curve this way: