In quantum physics, you can determine the angular part of a wave function when you work on problems that have a central potential. With central potential problems, you're able to separate the wave function into an angular part, which is a spherical harmonic, and a radial part (which depends on the form of the potential).

Central potentials are spherically symmetrical potentials, of the kind where V(r) = V(r). In other words, the potential is independent of the vector nature of the radius vector; the potential depends on only the magnitude of vector r (which is r), not on the angle of r.

So, when you have a central potential, what can you say about the angular part of

The angular part must be an eigenfunction of L2, and the eigenfunctions of L2 are the spherical harmonics,

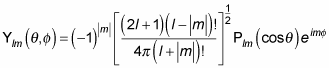

(where l is the total angular momentum quantum number and m is the z component of the angular momentum's quantum number). The spherical harmonics equal

Here are the first several normalized spherical harmonics:

That's what the angular part of the wave function is going to be: a spherical harmonic.