If you have a number of solutions to the Schrödinger equation, any linear combination of those solutions is also a solution. So that’s the key to getting a physical particle: You add various wave functions together so that you get a wave packet, which is a collection of wave functions of the form

such that the wave functions interfere constructively at one location and interfere destructively (go to zero) at all other locations:

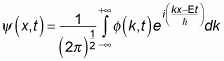

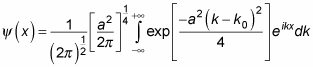

This is usually written as a continuous integral:

What is

It’s the amplitude of each component wave function, and you can find

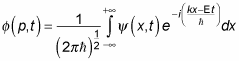

from the Fourier transform of the equation:

Because

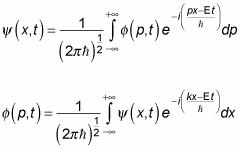

you can also write the wave packet equations like this, in terms of p, not k:

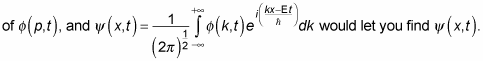

Well, you may be asking yourself just what’s going on here. It looks like

That looks pretty circular.

The answer is that the two previous equations aren’t definitions of

they’re just equations relating the two. You’re free to choose your own wave packet shape yourself — for example, you may specify the shape

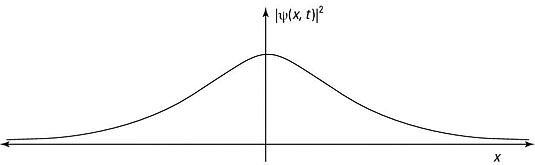

Here’s an example in which you get concrete, selecting an actual wave packet shape. Choose a so-called Gaussian wave packet, which you can see in the figure — localized in one place, close to zero in the others.

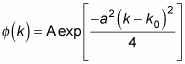

The amplitude

you may choose for this wave packet is

You start by normalizing

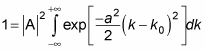

to determine what A is. Here’s how that works:

Substituting in

gives you this equation:

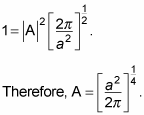

Doing the integral (that means looking it up in math tables) gives you the

following:

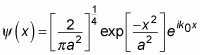

So here’s your wave function:

This little gem of an integral can be evaluated to give you the following:

So that’s the wave function for this Gaussian wave packet (Note: The exp[–x2/a2] is the Gaussian part that gives the wave packet the distinctive shape that you see in the figure) — and it’s already normalized.

Now you can use this wave packet function to determine the probability that the particle will be in, say, the region

The probability is

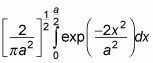

In this case, the integral is

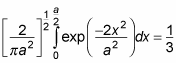

And this works out to be

So the probability that the particle will be in the region

Cool!