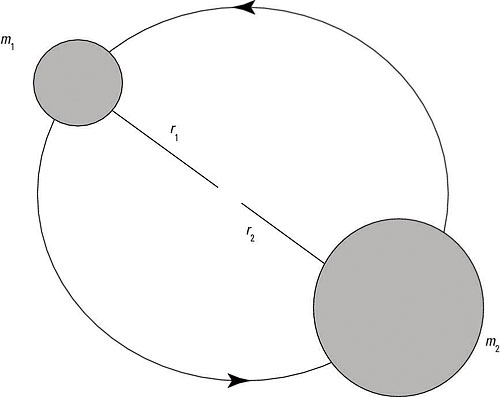

Here’s an example that involves finding the rotational energy spectrum of a diatomic molecule. The figure shows the setup: A rotating diatomic molecule is composed of two atoms with masses m1 and m2. The first atom rotates at r = r1, and the second atom rotates at r = r2. What’s the molecule’s rotational energy?

The Hamiltonian is

I is the rotational moment of inertia, which is

where r = |r1 – r2| and

Because

Therefore, the Hamiltonian becomes

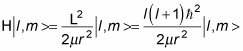

So applying the Hamiltonian to the eigenstates, | l, m >, gives you the following:

And as you know,

so this equation becomes

And because H | l, m > = E | l, m >, you can see that

And that’s the energy as a function of l, the angular momentum quantum number.