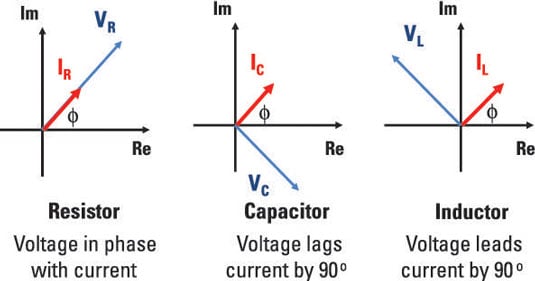

Use the concept of impedance to gernalize Ohm’s law in phasor form so you can apply and extend the law to capacitors and inductors. After describing impedance, you use phasor diagrams to show the phase difference between voltage and current. These diagrams show how the phase relationship between the voltage and current differs for resistors, capacitors, and inductors.

Ohm’s law and impedance

For a circuit with only resistors, Ohm’s law says that voltage equals current times resistance, or V = IR. But when you add storage devices to the circuit, the i-v relationship is a little more, well, complex. Resistors get rid of energy as heat, while capacitors and inductors store energy.

Capacitors resist changes in voltage, while inductors resist changes in current. Impedance provides a direct relationship between voltage and current for resistors, capacitors, and inductors when you’re analyzing circuits with phasor voltages or currents.

Like resistance, you can think of impedance as a proportionality constant that relates the phasor voltage V and the phasor current I in an electrical device. Put in terms of Ohm’s law, you can relate V, I, and impedance Z as follows:

V = IZ

The impedance Z is a complex number:

Z = R + jX

Here’s what the real and imaginary parts of Z mean:

The real part R is the resistance from the resistors. You never get back the energy lost when current flows through the resistor. When you have a resistor connected in series with a capacitor, the initial capacitor voltage gradually decreases to 0 if no battery is connected to the circuit.

Why? Because the resistor uses up the capacitor’s initial stored energy as heat when current flows through the circuit. Similarly, resistors cause the inductor’s initial current to gradually decay to 0.

The imaginary part X is the reactance, which comes from the effects of capacitors or inductors. Whenever you see an imaginary number for impedance, it deals with storage devices. If the imaginary part of the impedance is negative, then the imaginary piece of the impedance is dominated by capacitors. If it’s positive, the impedance is dominated by inductors.

When you have capacitors and inductors, the impedance changes with frequency. This is a big deal! Why? You can design circuits to accept or reject specific ranges of frequencies for various applications. When capacitors or inductors are used in this context, the circuits are called filters. You can use these filters for things like setting up fancy Christmas displays with multicolored lights flashing and dancing to the music.

The reciprocal of impedance Z is called the admittance Y:

The real part G is called the conductance, and the imaginary part B is called susceptance.

Phasor diagrams and resistors, capacitors, and inductors

Phasor diagrams explain the differences among resistors, capacitors, and inductors, where the voltage and current are either in phase or out of phase by 90o. A resistor’s voltage and current are in phase because an instantaneous change in current corresponds to an instantaneous change in voltage.

But for capacitors, voltage doesn’t change instantaneously, so even if the current changes instantaneously, the voltage will lag the current. For inductors, current doesn’t change instantaneously, so when there’s an instantaneous change in voltage, the current lags behind the voltage.

Here are phasor diagrams for these three devices. For a resistor, the current and voltage are in phase because the phasor description of a resistor is VR = IRR. The capacitor voltage lags the current by 90o due to –j/(ωC), and the inductor voltage leads the current by 90o due to jωL.

Put Ohm’s law for capacitors in phasor form

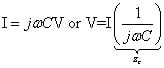

For a capacitor with capacitance C, you have the following current:

Because the derivative of a phasor simply multiplies the phasor by jω, the phasor description for a capacitor is

The phasor description for a capacitor has a form similar to Ohm’s law, showing that a capacitor’s impedance is

Earlier, you saw a phasor diagram of a capacitor. The capacitor voltage lags the current by 90o, as you can see from Euler’s formula:

Think of the imaginary number j as an operator that rotates a vector by 90o in the counterclockwise direction. A –j rotates a vector in the clockwise direction. You should also note j2 rotates the phasor by 180o and is equal to –1.

The imaginary component for a capacitor is negative. As the radian frequency ω increases, the capacitor’s impedance goes down. Because the frequency for a battery is 0 and a battery has constant voltage, the impedance for a capacitor is infinite. The capacitor acts like an open circuit for a constant voltage source.

Put Ohm’s law for inductors in phasor form

For an inductor with inductance L, the voltage is

The corresponding phasor description for an inductor is

The impedance for an inductor is

ZL =jωL

Earlier, you saw a phasor diagram of an inductor. The inductor voltage leads the current by 90o because of Euler’s formula:

The imaginary component is positive for inductors. As the radian frequency ω increases, the inductor’s impedance goes up. Because the radian frequency for a battery is 0 and a battery has constant voltage, the impedance is 0. The inductor acts like a short circuit for a constant voltage source.