Change things up to success in manufacturing

As with many things in life, success in manufacturing is about embracing change. Lean manufacturing pundits call this Kaizen, the Japanese word for continuous improvement, while others call it common sense. Either way, continuous improvement means taking small steps forward, fostering employee involvement, and providing metrics with which to measure the efficacy of incremental changes. This is the path by which people and companies alike thrive, no matter what they produce.Aside from “Kaizen events,” Lean also offers tools such as the DMAIC method (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control), The 5 Whys (repeatedly asking “why” until a root cause is revealed), PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act, which is also known as the Deming Cycle), and others. Call it what you will and use whatever tools are needed, but Lean is a necessary aspect of company and employee growth.

Acceptance of the status quo spreads like a disease in most environments, and manufacturing is no exception — creativity is stymied, all thoughts of continuous improvement quashed. But what’s a creative company or its subset of “let’s move forward” employees to do in the face of a larger workforce that’s afraid of change?Companies should strive for a culture of change, one that builds on the skills and knowledge of existing personnel. This means encouraging employees to constantly search for improvement opportunities. Get them excited about new technologies, and show them the benefits — financial, occupational, and social — of joining the let’s-make-our-company-the-best-it-can-be club. Then turn them loose to do their jobs. You might be pleasantly surprised with the results.

Adopt new technology to become a better fabricator

The best examples of continuous improvement are those that either improve part quality or increase the number of parts completed each day (or both). One way to start this most important of Kaizen changes is by talking to your tooling supplier. These are the guys and gals who spend their days traveling to different shops and get to see firsthand what works and what doesn’t, who attend routine company-sponsored seminars on new manufacturing technologies, and whose paychecks are often dependent on making their customers successful.For example, press-brake crowning systems are a great way to reduce setup time. Wheel tools for turret punch presses and tool coatings, for example, do not require a massive investment and improve productivity. Take a look at this figure for another cool example.

Courtesy: WILA

Courtesy: WILAModern press-brake tooling systems integrate with the machine controller to guide the operator through machine setup.

Convinced to give the latest widget a try? Don’t do it willy-nilly. Testing any new technology must be done scientifically. No matter how small, document each change and record the results. Keep track of setup and cycle times (something you should be doing anyway) before and after the change. Analyze how the investment improved part quality or tool life and then validate that it will pay for itself in a reasonable time frame. And above all, document, document, document — if not, you or someone else in the shop will end up reinventing the wheel six months from now.

If you’re not receiving regular advice and suggestions on ways to improve your metalworking operations from your tooling supplier, it might be time to look for a new one (or at least a new salesperson). Partnering with these and other industry experts is just one of the many ways to gain the upper hand over your competition, whether it’s the shop down the street or the one overseas.

Market your fabrication business vertically

What’s vertical integration? If you had a stainless-steel DeLorean, you could accelerate to 88 miles per hour and emerge in a simpler past, when machine shops machined parts and fabricating shops bent, formed, and welded them. But for many manufacturing companies, those easier days are over — their customers prefer the economy and convenience of a single source for their production needs, and want suppliers that can provide finished products, even if that means they must master fabricating, machining, painting, testing, and assembly, all under one roof. That’s vertical integration.For original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and their Tier I and Tier II suppliers, this isn’t simply a “one throat to choke” mentality (although that’s certainly part of their motivation). Single-sourcing one’s manufacturing needs to a qualified, multi-talented supplier is smart business. Done properly, it simplifies the procurement process and reduces product lead times. It strengthens the customer–supplier relationship. Engineering teams on each side of the fence are more likely to collaborate, increasing the likelihood of product improvements and cost reductions all around.

The moral of the story is simple: The most successful shops are (or soon will be) those that embrace all types of metalworking, as well as supporting processes such as plating, painting, powder coating, and assembly. They have learned to cross the party line and become masters of parts production technologies. This means future metalworking companies will offer bending, forming, stamping, and machining capabilities, assuring cost-effective and on-time delivery of quality products to whatever customer is asking for them.

Shorten setups, increase uptime in fabrication

Shops in the United States, Canada, and Europe are routinely expected to produce small orders of parts with minimal lead time and do so at a competitive price. The result? Setup times are becoming a proportionally larger factor in the “how much does this part cost to produce?” equation.Unfortunately, the ability to set up a job in minutes rather than hours is largely dependent on the type of tooling and software that is used. For example, quick-change tooling can be installed on most any press brake, as can systems that guide even unskilled operators through correct punch and die placement. Similarly, offline programming and simulation software eliminates hours of machine downtime. All are important aspects of setup-time reduction, but be warned. They require sizable investments and no small amount of planning.

The same can be said for turret punches, stamping presses, and virtually any other machine tool on the production floor. At the end of the day, setup-time reduction is a technical hurdle that all shops must overcome (assuming they wish to grow and be successful) and should be a top priority for anyone setting up multiple jobs per week.

Yet like most continuous improvement efforts, the challenge is as much organizational as it is technical. Quick-change tooling may allow shops to set up a brake in less time than it takes to eat a turkey sandwich, but it’s important to recognize that there are plenty of steps you can take to reduce setup times and make throughput more predictable and do so without spending a dime.

Much of this comes down to organization. Take a look at your tooling. Is everything in its assigned place? Look not only at the tooling in the crib (you have a tool crib, right?), but also the tooling that’s actually in the machinery or sitting about on the shop floor (there shouldn’t be much of this). Do all of the tools have a serial number and are they tracked in a TMS? (TMS is short for tool management system.) How about your setup sheets? The work instructions?

Maintain the machine (and tools)

A significant chunk of the organization just discussed involves routine maintenance of tooling and machinery. Here are a number of “best practices” shops should follow if they’re to keep everything in tip-top shape (the figure offers another example):- Clean, disassemble, and inspect all tooling for damage and wear after use. Replace worn springs, stripper plates, washers, and so on as appropriate.

- A small amount of lubricant or rust preventative should be applied periodically to metal surfaces to avoid corrosion.

- Always use a torque wrench rather than a best guess with your arm to tighten things down.

- Air and oil filters should be replaced religiously. The same goes for hydraulic fluid.

- Routinely check back gauges and ram surfaces for parallelism and squareness.

- Periodically inspect electrical connections and other fasteners for tightness (be sure to use OSHA–approved lockout-tagout procedures).

- If you don’t have a George on staff (and even if you do), machines should be inspected annually by a factory-certified machine tool technician.

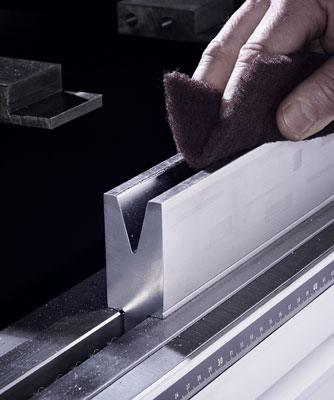

Courtesy: WILA

Courtesy: WILACleaning, lubricating, and properly storing your tooling is key to predictable manufacturing processes.

If possible, it’s best if punches, dies, and other tooling are assigned to a specific machine and kept there. This isn’t always feasible, but it does keep the inevitable wear patterns of the locating surfaces matched, providing more consistent results than bouncing tooling all over the shop like a kid without a date at the high school prom.

Lastly, remember that toolholder life is finite. Most experts will tell you that tooling should be replaced every few years, depending on how much action they see (the toolholder, not the experts). They’re not just trying to sell more stuff. Metal fatigues over time, causing problems with part accuracy and tool life. If you have tooling approaching its teen years (and in heavy-use cases, much younger than that), it could be time to send it out for reconditioning, or to the recycler.Manufacturing is not a dirty word

Ask any shop owner to describe his or her biggest obstacle to company growth and most will tell you the same thing: finding qualified people. For whatever reason, manufacturing has grown less popular as a career choice over the past few decades, despite the increasing demand, better technology, and higher wages.A Google search of manufacturing wages in 2017 reveals that average salaries are approaching $50,000 per year in the United States, substantially more than photographers, medical technicians, fitness trainers, and embalmers. Granted, you don’t get to wear a leotard or make dead people look nice for grieving relatives, but manufacturing is a good-paying, rewarding career that lets you make cool parts and play with robots.

For those with an eye toward upward mobility, a fabricating career is a gateway to even more challenging vocations such as machine-tool programming, applications or manufacturing engineering, tool and die design, equipment sales, or even going into business for yourself. Contrary to what the media has been saying, all the manufacturing work hasn’t gone to China. Yes, parts are less expensive to produce in countries with low labor costs, but those companies that have tried sourcing parts based solely on price frequently (and painfully) discover that the old adage, “you get what you pay for” is abundantly true.

The result is that many of the products that have gone offshore over recent years are now being re-shored. Procurement people, tired of long lead times and questionable promise dates, are sourcing more parts on this side of the ocean. Quality is difficult to control when parts are made thousands of miles away, with late-night or early-morning meetings to resolve complaints the norm. And consumers recognize that “buying local” is good for them and their neighbors. Long story short, manufacturing is back, whether you work in Milwaukee or Minneapolis, Magnolia or Manhattan Beach.

Forget about what you may have heard. Manufacturing is a high-tech, clean, and lucrative profession. If you’re interested in it and have even a smidgeon of mechanical aptitude, chances are good you can find a shop willing to take you on. If you’re thinking about college but aren’t sure what you want to be when you grow up, skip the philosophy major, the burdensome student loans, and walk, bike, or take an Uber to the nearest technical college. And if you’re already skilled and are looking for a better job, get busy knocking on doors. The manufacturing waters are warm; come on in.

Become certifiable

Perhaps the best way to become one of the qualified people just discussed is to attend vocational school. Working one’s way up the ladder isn’t the worst way to learn a trade, although doing so requires an inquisitive mind, an abundance of patience, and the ability to put up with the hooting and hollering from your coworkers after crashing a machine (not to mention a stern talking-to from the owner).The Society of Manufacturing Engineers (SME) says the average manufacturing worker in the United States earns more than $77,000 annually. That’s pretty good coin, yet fewer than 40 percent of the parents of school-aged children think their kids should pursue a career in manufacturing. Worse, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) says that 3.5 million manufacturing jobs will be needed over the next decade, but 2 million will go unfilled due to a shortage of workers. Still think that Bachelor of Fine Arts degree you’ve been pursuing is a good idea?

For those of you who’d rather avoid the trials of learning on the job, there are plenty of training options available. Aside from vocational-technical schools (most of which offer excellent one- to two-year programs), a number of online classes exist:- The Society of Manufacturing Engineers has developed its Tooling-U SME series of training materials. These include instructor-led and self-paced classes, on-demand e-books and videos, and industry-recognized certifications to demonstrate achievement.

- The Fabricators and Manufacturers Association (FMA) offers people an opportunity to earn its Precision Sheet Metal Operator (PSMO) certification, which covers important skills such as laser cutting, punch press operation, metal finishing, and a whole bunch of other stuff I discuss throughout this book.

- The American Welding Society (AWS) is just one of the organizations providing accreditation in this highly technical trade. Enrollees can pursue certification as a welder, inspector, engineer, radiographer (sort of like an industrial X-ray technician), and more.

- SolidWorks, a leading developer of CAD software, offers the “Certified SOLIDWORKS Professional Advanced Sheet Metal” (CSWPA-SM) exam to test the ability of those designing sheet-metal components. Similarly, CAD giant Autodesk offers its ACP certification (short for Autodesk Certified Professional). Both are great ways to increase your value to potential employers.

You might be the top dog at your shop, but remember this: There’s always more to learn (and other dogs nipping at your heels). Manufacturing is a deep, ever-changing topic, and no one masters all of it, ever. If you’re not taking online classes, attending seminars, or at least reading books and trade publications, you’re falling behind. And saying your company doesn’t pay for it is no excuse. For starters, you’re unlikely to get a job working for someone that will pay for it if you’re going to sit on your hands complaining. Second, there’s plenty of free or almost-free information out there — subscribe to magazines, buy a For Dummies book, or take some night classes on your own dime. Just get learning. You won’t regret it.

Don some cool safety shades when working in manufacturing

The shop floor can be a dangerous place, especially for those not paying attention to what you are doing. Here’s some other things to watch out for:- Having your eye scraped by an emergency room doctor to remove tiny bits of metal and the rust rings they created while you were sleeping is a memorable experience. The way to avoid it is clear: Always wear your safety glasses, preferably the dorky-looking ones with side shields. If you’re grinding, wear a face shield. Failure to do so may give you a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to learn Braille.

- Similarly, the bright blue light created by an arc welder might seem very pretty, but looking at it (even a sidelong glance) is another way to damage your eyesight. Always wear top-notch welding goggles, and if you’re around someone who’s welding, shield your eyes or look away.

- It might not be as strenuous as an afternoon at the gym, but fabricators often need to lift heavy objects such as die sets and heavy workpieces. If you’re not wearing steel-toed boots, you’re asking for trouble. And if you’re wearing flip flops, please go home.

- Gloves are quite necessary for welding and many other sheet-metal activities, but if you wear them while operating a milling machine or other rotating machinery, you might end up with a resulting injury called degloving (ironic, right?), whereby a large piece of flesh is separated from the surrounding area. Ouch.

- Speaking of stylish accoutrements, what are you wearing? Are your sleeves rolled up? If not, it’s fairly easy to get one caught in a piece of machinery. That’s true for long hair as well. Guys and gals alike need to keep their hair short, put it in a ponytail, or wear one of those trendy black mesh hairnets.

- If you’d like to hear the laughter of your grandchildren, the sound of the wind through the pine trees on a winter day, and avoid your spouse having to nag you non-stop to turn down the television, always wear ear protection around metalworking machinery.

Another dumb idea is removing safety guards from equipment, or not locking out the electrical panel before performing preventative maintenance.

Keep your fabricating shop or house in order

Let’s face it — some fabricating shops are just plain dirty. Hunks of scrap metal and grinding dust surround the welding area. Hydraulic fluid drips from the back of the press brake. There’s trash in the aisle, tooling catalogs scattered about the break room, the machinery hasn’t been wiped down in months. What a pigsty!It’s more than appearances, though. Cleanliness is also about safety. The risks that come with slippery, trash-strewn floors are real, especially around sharp and often heavy workpieces. Air quality is also a concern. Welding and cutting gases should be controlled at all times; paint fumes and powder coating dust must be properly evacuated. Failure to do so may leave shop management wondering someday if they’re partially to blame for Wayne’s lung cancer or Mary Beth’s emphysema.

There are also the machine tools to consider. Good housekeeping goes well beyond filter replacement or checking for axis wear — it means keeping the shop’s expensive and highly accurate equipment cleaner than the antique car you have sitting covered in your garage. And while the employees might not complain (too much) when the shop hits 90 degrees in July or is cold enough that you can see your breath come February, temperature swings are tough on equipment. Keeping the shop at a consistent temperature year-round is less expensive than remaking scrap parts or training new employees, never mind the benefit to its CNC machines.The bottom line is that successful manufacturing companies embrace employee safety, cleanliness, air quality, and all the things that make a shop environment pleasant to work in. Equipment lasts longer. Employee morale is better than in “piggy” workplaces. Visiting customers spread the word to others, “I’ve never seen such a clean shop, they must really be serious about quality,” thereby increasing the likelihood of new business. Dirty, hot, or dangerous shops? There’s really no reason for it. Get sweeping.